I have always looked to find love online. Squeezing words through fiber optics to try and reach through the screen—to lace hands, to comfort, to talk through the things lost in time delays and bad dial-up connections. 2003-era LiveJournal primed me to receiving digital love, and now, like a junkie reminiscing about the “softer stuff”, I’m nostalgic for its design affordances. On LiveJournal, the only way to acknowledge, express approval, or “hate-like” something was by leaving a comment. Responding through text suggests nuance, and in this way, expands past the binary of “liked” or “not liked.”

In Erich Fromm’s classic (yet overly conservative and, by today’s standards, sexist) The Art of Loving, there is a chapter about the conceptual differences between motherly and fatherly love. I’ve found Fromm’s ideas useful as an analogy for social networks and algorithmically controlled social structures. He claims that as a child matures and takes her place in society, she is simultaneously moving from the realm of motherly, unconditional love, into the realm of fatherly love. Here, she must fulfill the prerequisites of patriarchy’s conditions in order to earn love. Similarly, the digital affirmations we receive throughout the day can feel like a simulacra of unconditional love—until we’re bereft of these affirmations, and we realize we have to constantly work to earn them.

Despite believing the enduring myth that the internet was created to be free, commercial ISPs formed only a few years after the WWW was invented. In 2018, love in the cloud is cheap to give and receive, and easy to mine and exploit. So where is unconditional, genuine love and affirmation in the cloud—and how hard do we need to squeeze it to get a drop? How might we keep our acts of love on the internet expansive, protected, and corporeal? My explorations of these questions start here.

The cloud is tangible

24x24 pixels worth of hearts and thumbs-ups are at the tips of our trigger fingers, and traded on a marketplace like commodities with decreasing value. Sending vectorized (infinitely scalable and replicable) abstractions of our feelings is now a tic—when we press the button we are acting on a neurological impulse to make known our identity, affiliations, and aspirations.

My late, ever-prescient friend Crystal Ruth Bell (maybe with a name like “Crystal Bell” it’s hard not to be ever-prescient) experimented with making social media tangible, way before this conversation mattered. On a 10-day trip together, we backpacked through fog-heavy and romantic areas in the Southwest of China. In her already bursting bag, she stuffed a crusty, leaky jar of DIY wheat paste, plus a series of blown-up printouts of the 2010-era blue Facebook thumb, and the now-phased-out “You like this” text. I was cranky and wary when, during our long days out, she would stop every once in a while to dig up her tools and leave her mark.

Today, searching for documentation of her leaving her mark meant I had to enter the landmine of her In Memory Facebook profile—something I’ve not been able to do since she passed. I say landmine, but I guess it’s more like quicksand. The longer the lingering, the deeper the sink.

Crystal Ruth Bell's Facebook wheatpastes

✶✶

Sort by: love

Facebook’s Friendship Anniversary feature may be the closest thing we have to platform-level social media sentience about love and intimacy. Now though, any positive emotions we’ve associated with it are tainted by the thought that that memory, shared between friends, contributed somehow to the election of what Thor Harris, in another piece on The Creative Independent, called a “chapped scrotum.” As such, it’s important to remember: just because platforms like Facebook have been made to comprehend correlations in data columns that represent patterns of intimate human behavior, doesn’t mean they know how to love.

Twitter user あき@相談屋さん

✶✶

“It’s Aki! I’m here to listen to everyone’s thoughts about wanting to die or to disappear. I myself was once a young girl, a wrist-cutter who did enjo kosai [compensated dating] because I felt like I didn’t belong anywhere. I wish to hear all of your stories so we can find an answer together!”

I’m fascinated by Twitter users like Aki@Soudanya, who seem to channel their emotional energy online in order to give absolute strangers a shoulder to tweet on. There’s a rash of these accounts that are especially active on Japanese twitter, who add the words “相談屋 soudanya” to denote that their accounts are run by people trying to fill the role of free online counseling.

And what does a social media platform know about the opposite of love, by virtue of being flooded with hate on an ongoing basis? What can a platform know about how to evaluate negativity against negativity? Might it ask, “Is this instance of harassment, vitriol, or threat of rape or death worse than that other one?” Are the standards gradually lowered? Does the idea of rating content based on how loving (or un-loving) it is sound completely idiotic? Would the standards rise in a competition to out-love each other—this comment doesn’t show care and affection as much as the other!—if this were the case?

Taeyoon Choi and the School for Poetic Computation led a hands-on investigation into distributed networks of care.

✶✶

The answers to many of these questions come down to who is making the call on whose love is protected, and how. As such, we may never find any answers. So maybe it’s best to take matters into our own hands.

Do not underestimate the people pleaser’s potential for distributed cyber-care.

For the Library of Practical and Conceptual Resources, I’ve created a list of “action items” you can perform when you feel let down by the limitations of the digital embrace. As you perform these actions, keep the following in mind:

- Do not overestimate how much love you deserve.

- You must show love in order to receive it.

- When you first start performing love online, you don’t even have to mean it at first. Know that building up a second-nature behavior is as much about following a steadfast routine as it is about developing a naturally occurring instinct.

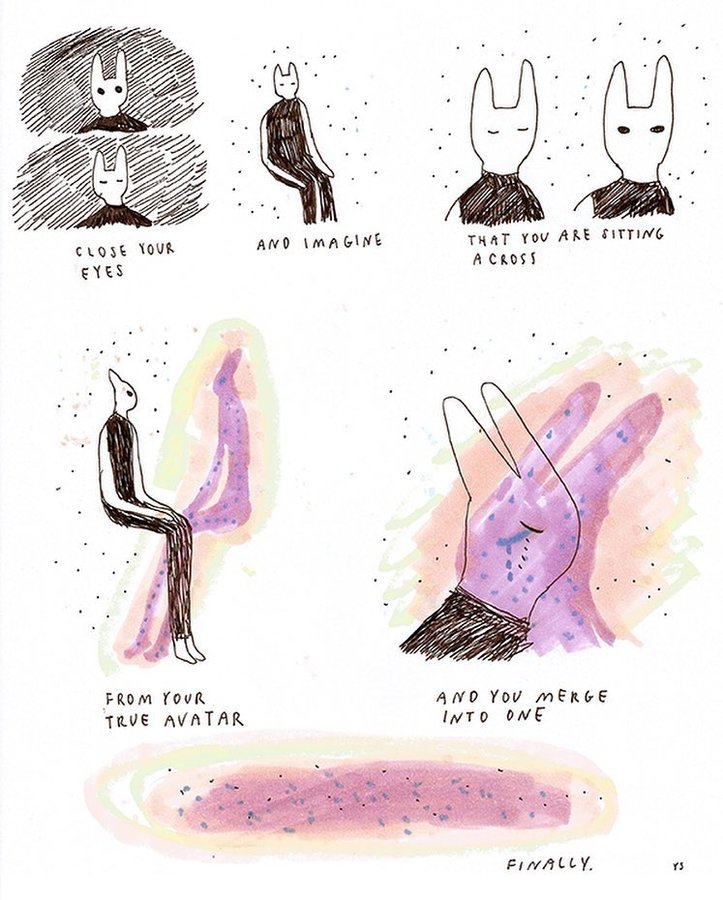

Image credit: Yumi Sakugawa